|

|

|

Blossoming

of Silicon Valley

After five years and many interviews, the book Roots and Offshoots: Silicon Valley’s Arts Community is finally published. It contains four essays, twenty profiles, 53 color and 28 black-and-white images. Developed with editors Nancy Hom and Ann Sherman, the book also contains guest essays by Maribel Alvarez and Raj Jayadev.

Future projects include an online book; further development of collaborations for research and activism; and meaningful ways to engage academia, policy makers, and community. For updates and to purchase a book, visit www.gingerpressbooks.com. Distributed by Bolerium Books, San Francisco. Ohlone Art and Building Community

Thoughts, first posted September 2014, on how the diversity of Ohlone art and its uses relate to basic cultural values and relationships, then and now. We welcome your feedback.

Ohlone art making and usage once reflected their lifestyle in sync with nature, their community organization and functioning, their understanding of the sustenance and healing powers of plants and herbs, their relationships with animals and the spirit world. What can be learned from ancestral and present-day Ohlone Indians? What questions can be raised by and further research conducted by students of art, anthropology, archeology, history, government, ethics, and more? And for today's policymakers? Ancestral Ohlone Art

For over 10,000 years the ancestors of today's Ohlone Indians created art in what is now known as Silicon Valley. They wove baskets for leaching acorn meal, cooking, fishing, and winnowing grain; and for storing ornaments of abalone, cut-and-drilled beads from Olivella shells, and complex feather dance regalia—all part of community life, whether everyday, social, and/or religious. Photos: Joe Cavaretta (Muwekma Tribe) Kuksu ceremonial pendants, c. AD 1100-1600. Kuksu ceremonial pendants from the Muwekma Ohlone ancestral heritage site CA-ALA-329, located in Coyote Hills East Bay Regional Park, are similar to those found in downtown San José made of red and black abalone shells. Charmstones, body paint, and Olivella shell beads were also part of the Kuksu religion and Ohlone art. Such art was related to shamanic visions and ceremonial religious performances. CA-ALA-329 dates from 150 BC to AD 1767 and was continuously used as a ceremonial mortuary mound for the ancestral Muwekma Ohlone nobility (men, women, children) and fallen warriors.

Photos: Joe Cavaretta (Muwekma Tribe) Sandstone charmstones, red paint mortar, and Olivella shell beads. While natural resources were shared, certain art forms were owned. Jewelry (shell ornamentation and regalia) was associated with status and wealth based upon the family's lineage and ranking in the community. Art and cultural objects were cherished.  Photos: Alan Leventhal

Photos: Alan LeventhalStone Smoking Pipes (Torepa) and Elk Antler Harpoons .

Photos: Alan Leventhal

Photos: Alan LeventhalCalifornia Indians wove baskets with geometric designs and made pictographic (painted) and petroglyphic (pecked) rock art. The art skills of Ohlone people grew by encounters with and learning from people of neighboring cultures and language families. Aided by having skilled navigators and craft specialists and distance traveling, they traded, observed and developed complex forms of art. Some of their arts are not so obvious. The arts of healing; landscape management (periodic burning of the land); preserving habitat for natural foods and herbs; the arts of hospitality; of music and storytelling; of sharing resources; of home, boat, and sweatlodge (tupen-tak) construction using natural materials; and the arts of survival; the art of building community—living communally, at times and in some aspects, in an egalitarian society as far as women were concerned, with respectful gender and generational relationships. Mission Times, Interactions

Once widely known for the finest baskets, Ohlone women lost much of their material and spiritual culture when they labored in the valley's emerging agricultural economy. With the establishment of Spanish ranchos and an increasing hide trade, the decimated Ohlone population became a hidden minority, their native way of life increasingly influenced by Spanish/Mexican culture. Many Euro-American leaders with cultural and gender prejudices (U.S. women's right to vote didn't come till 1920 and women are still excluded from many religious and business leadership roles) did not accept the egalitarian nature of Indian society with respect to women, or that an Indian woman could have leadership responsibilities and high status, and they ignored or devalued Ohlone women's skills. Their traditional arts would take a long time to recover, because the evolving arts of survival and new art forms for community building took precedence.

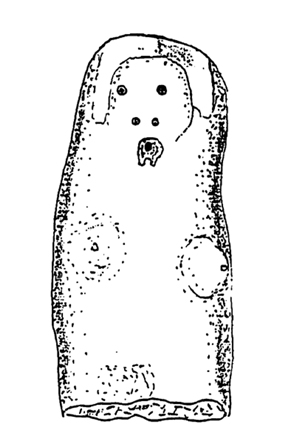

Indians at local missions did learn to produce many different types of art and crafts, such as leather arts: saddles, bridles, whips, shoes and boots. Indian men could become full-time musicians, with training from boyhood. Indian girls were not afforded the opportunity. Organs, strings, winds, and percussion instruments were used. Indians also made some of their own instruments, such as a violin (San Antonio de Padua Mission, Monterey County). In 1809, Mission San José had an Indian ensemble of 30 singers, accompanied by an orchestra. For their new church dedication that year, musical director Padre Narciso Durán brought in the choir of Mission Santa Clara. Many Ohlone learned to make ceramics at Santa Clara Mission, although most of it was probably "utilitarian," including roof (tejas) and floor (ladrillos) tiles, but clay-fired products in the missions may have been another entry into new modes of art production. During pre-contact times, ancestral Muwekma Ohlone made anthropomorphic clay figures as part of the funeral ceremony.  Anthropomorphic Female Figure CA-ALA-329 (circa AD 1200-AD 1500) Native people decorated the interiors of mission churches in a mix of indigenous and Catholic designs. A hidden painted altar at Mission Dolores in San Francisco was created around 1791 by Indian laborers in a dry fresco technique using natural pigments, and included Catholic iconography. A composite image pieced together from 300+ photographs shows the top 22' x 5' section. The ceilings of many local mission churches were painted with red and white zig-zags, which was probably a traditional native basketry and rock art motif.

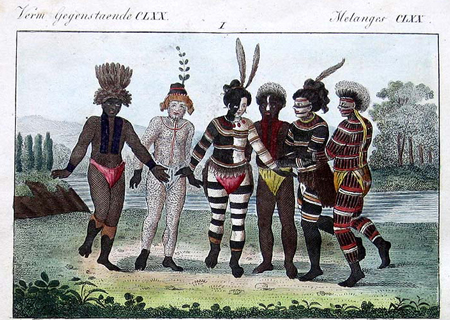

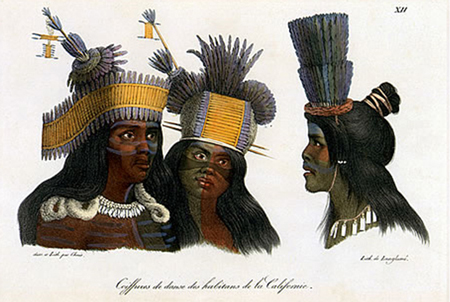

Images: Ben Wood and Eric Blind Composite image of hidden mural at Mission Dolores, c. 1791, painted by Indian labor.Detail of heart pierced by three daggers. At Mission Santa Clara de Asis, Thamién Ohlone-speaking women turned to weaving and fabricating cotton clothing, blankets, and carpets for the community, including ecclesiastical garb such as somber, matte velvet funeral vestments. It was difficult for native people to continue their own "traditional" arts like ceremonial regalia in the missions due to the policies of the Franciscans. However, we know from the archaeology that native people continued to use Olivella and clamshell beads, abalone pendants, and also incorporated new ornamentals such as glass beads. They probably had baskets too, but those do not preserve well in the ground—which is unfortunately a last resource, considering what happened next.  Von Langsdorf Sketch of Indians at Mission San José in 1806.  Louis Choris, 1816 Indian Women, Tattoed Chins, Mission-style Clothes. Mission Dolores.  Louis Choris, 1816 Indian Men, Mission-style Clothes. Mission Dolores.  Louis Choris, 1816 Sketch of Ohlone Indian men in regalia (while on the Russian expedition ship Rurik at Mission Dolores). The Gold Rush and statehood were followed by 18 unratified treaties (1851-1852), government neglect, broken promises, genocidal policies, racism, scapegoating, and loss of their environment and their legal rights. Basic survival, for individuals and community, became the Ohlone art form, including places to seek refuge. Some local Ohlones found security on the Alisal rancheria in Pleasanton and at El Molino (the mill) in Niles. Modern Life Transitions

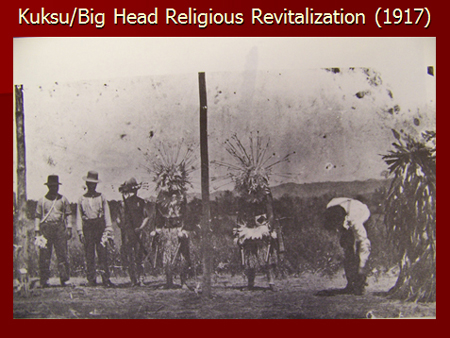

To maintain community values and interactions, Ohlone people strove to continue life patterns and traditions. Special events, such as religious revitalization movements that began in 1870 in Silicon Valley and other areas of Central California and continue today, employ regalia with abalone pendants similar to those found in the mounds.

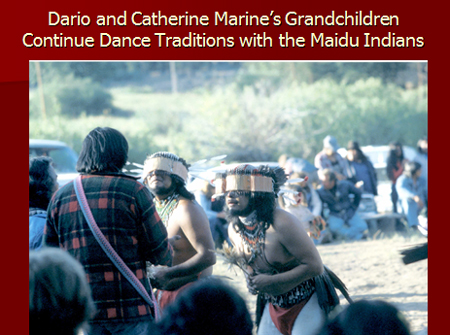

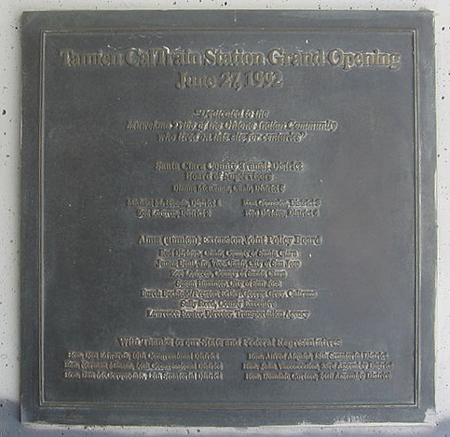

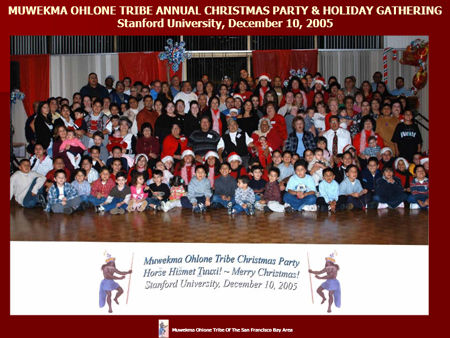

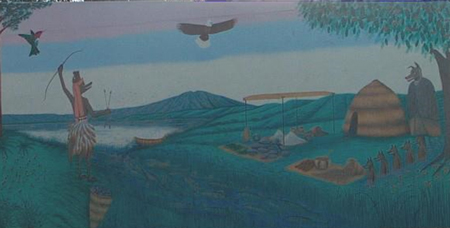

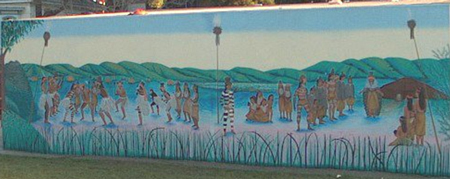

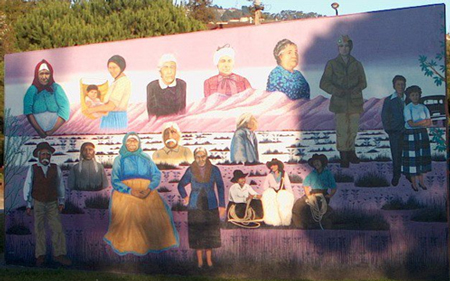

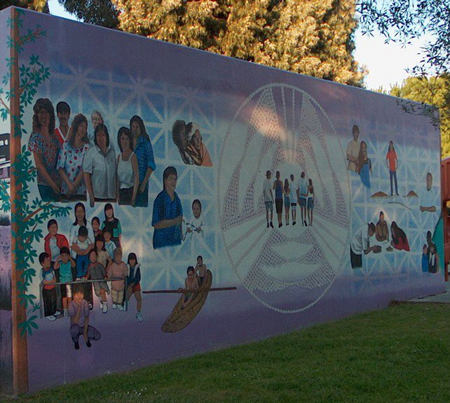

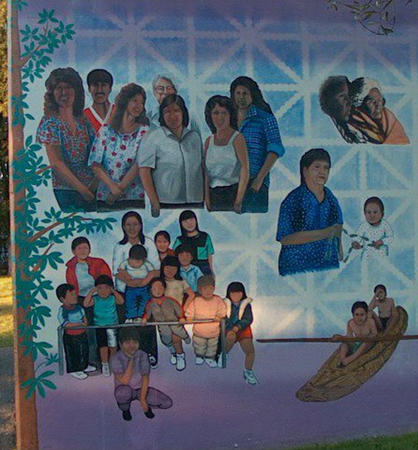

Kuksu Big Head Religious Revitalization. Stoney Ford, Sacramento River Valley, ca. 1917. The ancient Kuksu abalone pendants possibly represent Big Head Dancers (Spirit Impersonators). Angela Colos, born in 1839 to an Indian couple married at Mission Santa Clara in 1838, passed along many tribal traditions. Colos was also one of the principal linguistic consultants for many anthropologists. As a fluent speaker of the Chocheño Ohlone language, she shared her linguistic knowledge by stating that "muwékma," means "la gente (the people)." Her living descendants are enrolled members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area.  Maria de los Angeles (Angela Colos), c. 1925, at Alisal Rancheria between Pleasanton and Sunol. Mandy Marine (Mono/Maidu/Muwekma), great-granddaughter of Muwekma Ohlone Indians Dario Marine and Catherine Peralta Marine, continues the art of basketmaking her Mono Indian relations taught her. Marine's father still teaches the traditional dances that were related to the 1870 Ghost Dance religious revitalization movement that spread throughout central California.  Dario and Catheine Marine's grandchildren continue dance traditions with the Maidu Indians at the 1983 Bear Dance Renewal Ceremony (Joe Marine on the right).  Photo: Rob Yamane Linda Yamane. Linda Yamane, a 1978 MA graduate of San José State University and a descendant of a Monterey Bay area Indian woman from the late 1700s, has researched Ohlone weaving methods and demonstrated and created her own basketry (it can be viewed at the Oakland Museum). Over decades, Ohlone place names in Silicon Valley were replaced by Hispanic and Anglo ones—the politics and art of erasure by the dominant societies. Very few Native Ohlone place names are left. Tamien (Thamién) was the name of a village in the middle of the contemporary city of Santa Clara, or of a district of multiple villages surrounding Mission Santa Clara (1776). An Ohlone village name was given to the land grant Rancho Posolmi, awarded in 1844 to Lopé Inigo, an Ohlone connected to Mission Santa Clara; the indigenous name and history were later buried in the land's transformation into the aerospace site Moffett Field. A rare exception is Ulistac Natural Area in Santa Clara, which may mean "place of the basket" in several Ohlone languages. Ulistac was a land grant to three Mission Santa Clara Ohlone Indians. Attentive to archeological sites and respectful of native sites and burial grounds, Ohlones have reclaimed the arts of naming and installation. Caltrans and Santa Clara Valley Transportation Agency named the Tamien Station to honor the ancestors of the Muwekma Ohlone when construction of a railroad station in San José during the late 1980s uncovered a major ancestral heritage archeological site containing around 172 ancestors. They planned a permanent exhibition of artifacts found on the site, but that has not yet been constructed.  Photo: Pedro Xing Tamien Station, 1992, San José, named after the local Ohlone village.  Ulistac Natural Area, Santa Clara, (near the new Levi's Stadium). Research and action brought prominence to the 1791 Mission Dolores mural, hidden no more. A public painting of the mural was unveiled on Bartlett Street in 2011. To recreate the photographed section, local muralists Jet Martinez, Bonnie Reiss and Ezra Eismont collaborated with artist Ben Wood and Andrew Galvan, an Ohlone Indian descendant, curator of the Old Mission Museum.  Photo: LisaRuth Elliott Public painting of the hidden 1791 Mission Dolores mural, 2011.  Photo: Muwekma Tribe Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Christmas Party, Stanford University, 2005. The Bureau of Indian Affairs has documented over 500 members currently enrolled in the Muwekma Tribe, who gather in a variety of ways for celebration and for academic research, language revitalization, and community action including restoration of their federally acknowledged status. In addition to performance art and installations, the Ohlone now use public art to build community and to honor and celebrate native Ohlone history and heritage. Working with Muwekma, Amah-Mutsun and Esselen Nation Costanoan/Ohlone tribal communities, artist Jean LaMarr's 1995 mural (2013 restoration) The Ohlone Journey, located in Ohlone Park in Berkeley, celebrates Ohlone life and culture on four walls. For over four decades, LaMarr, a California Indian who lives in Susanville, has through her art helped people "understand our world."  Photo: Muwekma Tribe On the east wall, Coyote Creation Story depicts the abundance of life that once thrived in this region.  Photo: Muwekma Tribe The north wall depicts the dance with which the Ohlone welcomed the European Entry Into the Bay Area.  Photo: Muwekma Tribe On the west side, Modern Life Transitions, honors individuals who lived in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, depicting members of indigenous families based on photographs taken over the generations and lent to the artist by their descendant family members. Images of the elders include, far left, Muwekma Elder Angela Colos. Also included are Ascencion Solarsano de Cervantes (died 1930) and her mother Barbara Serra (Amah-Mutsun Tribal Band, Mission San Juan Bautista); anthropologist C. Hart Merriam collected baskets from both during the early 1900s, which are curated at University of California, Davis.  Photo: Muwekma Tribe  Photo: Muwekma Tribe On the south side, The Strong Walk Back to the Future represents the Ohlones' determination to thrive without sacrificing their traditions or cultural identity. Upper right from left to right is Chairwoman Rosemary Cambra and her mother Dolores Sanchez (Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area). For more information, visit the Ohlone Park website. Ohlone art production and usage suggest ways to re-experience community. Our Silicon Valley identity has picked up on many of these values in environmental art: respect for Open Space (thinking of our local Open Space trust, district, and projects; capitalization my own sign of respect) and environmentalism; lifestyles that are closer to nature; organic, even alternative healing methods; the beginnings of a return to natural habitat gardening and earlier natural ecosystems. But very little recognition of the role and continuity of Native California people exists.

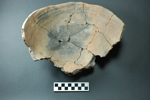

Beads and pottery fragments from the 3rd Mission Santa Clara, found next to the former Indian barracks where the Santa Clara Woman's Club is located today. Research continues at Santa Clara University, San José State University, and Stanford University. Art has continually been a part of community building for the local Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. A big chunk of the meaning of a basket or beads is lost when we lose or ignore the art object's closest community, the communal sphere in which it was created. How can we best acknowledge and support the art, the research, the discussion, and also the living community? These questions present academic, economic, religious, political, and ethical concerns. We need to examine the broader implications of the Ohlone story to the present day. SCU archeology professor Lee Panich asks: What's at stake? A popular view of Indians and Missions, so often recreated in 4th grade California History curriculum, architecture and tourism—a romanticizing of earlier eras, while cultural continuity and contemporary native presence is obscured or minimized and reduced to a historical record with selective representation and biases. Alan Leventhal, SJSU anthropology lecturer, mentions the Ohlone child in the classroom being told there are no more Ohlones left: "How does one undo this damage?" He calls attention to the fact that under federal law an Ohlone Indian artist cannot say s/he is a Native American artist as long as the Tribe is currently no longer federally acknowledged. The same applies at the Golden Gate National Cemetery; memorial headstones cannot acknowledge local Ohlone Native Americans who served in WWI and WWII. "How do we celebrate the human condition? Art is part of that. How do we celebrate a 10,000-year-old history and reach a wider audience?" Horše tuuxi [Hor-shay too-he] = Good Day ‘UTaspu meene [OO-t(r)as-pu mee-ne] = Take Care of Yourself, Goodbye Kiš horše ‘ek-hinnan [Kish Hor-shay ek-hean-nan] = Thank you © Jan Rindfleisch 2014 With appreciation to Alan Leventhal, San José State University; Dr. Lee Panich, Santa Clara University; and artist Jean LaMarr (Paiute and Pit River), Susanville.

More information: "Mapping Erasure," Les W. Field with Alan Leventhal and Rosemary Cambra, in Recognition, Sovereignty, Struggles, and Indigenous Right in the United States, A Sourcebook, edited by Amy. E. Den Ouden, and Jean M. O'Brien, 2013, University of North Carolina Press. Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants, The Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers, Kent Lightfoot, 2005, University of California, Berkeley. Ohlone Tribal Revitalization Movement, A Perspective from the Muwekma Costanoan/ Ohlone Indians of the San Francsico Bay, Les Field, Alan Leventhal, Dolores Sanchez, and Rosemary Cambra. California History 71:412-431. 1992. Visit the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe website. Websites: Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation |

| Copyright © 2013-25 Jan Rindfleisch. All rights reserved. |