|

|

|

Roots and Offshoots - The Blossoming of Silicon Valley's Arts Community

"Roots and Offshoots, the Blossoming of Silicon Valley's Arts Community," a cross-cultural, interdisciplinary essay, was first posted here in August 2014 and published in the Californian, Fall 2014. The revised essay is now the opening essay in the book Roots and Offshoots, Silicon Valley's Arts Community published in 2017.

For more information about historical San José area arts development, including the Silicon Valley Arts Council, and an overview of San José arts activity in the 1970s and early '80s, see "The First San José Biennial" essay, Jan Rindfleisch, for The First San José Biennial, 1986, San José Museum of Art.

The story of the development of the arts in Silicon Valley has just begun to be told. Its art history is filled with people who were often marginalized, people who stood up to the status quo, people with the guts and love to persevere and build a community that nourished all, at a time when that was not easy to do. It's time to tell the story.

How did we get from the largely monochromatic, exclusive, and repressive landscape of the 1970s to where we are now? In this article, I will introduce various elders and others who have contributed creatively to the blossoming of Silicon Valley, place them in a broader context of community building, and set the stage for individual profiles still being collected. We need context for current discussion, and for our historical documentation that is so easily lost—websites included. My intent is to raise questions and ideas about how the arts, community, and democracy can flourish in Silicon Valley. I suggest that academics, community leaders, artists, activists, and students can take action to enrich and document the arts forum across cultures, academic and professional disciplines, and economic sectors. This examination should consider new types of arts roots, startups, and offshoots. All can be incorporated into our Silicon Valley identity, already known for its innovative problem-solving culture. Despite the levels of complexity in our local art history, the tale remains instructive and relevant. For some of the people involved, the story of what they were up against and how they worked to change it is their legacy; for many more, it is what they continue to do. Common among all of them is a grounded connection to fundamental human concerns, plus an ability to relate to diverse communities. Let's begin to meet some of these fascinating people and see where a good heart can take us. The death of Consuelo Santos-Killins in 2012 was a wake-up call for me and other arts activists to start telling the story of arts community building in Silicon Valley. During her long lifetime, she was a key figure in the effort. She brought an overarching vision integrating art, socioeconomic issues, and politics, with an understanding of basic human needs, important for leaders and activists of any age. The vivacious redhead served on the San José Fine Arts Commission, the Santa Clara County Arts Council, and the California Arts Council, among other arts organizations. She argued for substantive arts programs in the schools and community, and more diverse participation in arts governing boards. Compassionate and generous toward all in need, Santos-Killins—once a nurse—did not limit her activism to the arts, but the arts remained foremost for her.1 San José Mercury News columnist Scott Herhold remembers, "You could talk to Santos-Killins about, say, the need for corporate directors to ask more questions, and before your talk was over, she would have convinced you utterly of the need for ceramics and music and painting in the schools." "The assumption is that quality exists only in highly visible cultural institutions—the truth is an abundance of artistic quality exists in Santa Clara Valley… As in San José, significant progress in the arts will occur when people speak up in order to change attitudes toward art—people who believe in the area they live in." — Santos-Killins Making an Arts Community

Building an arts environment requires energy, courage, and determination, but Santos-Killins wasn't the only one. Silicon Valley blossomed in the last quarter of the 20th century with the formation of arts offshoots, spin-offs, and startups that tapped into the area's increasing ferment of ideas and involved myriad supporters across all walks of life.2 Through my own long and varied involvement in the arts as an educator, presenter (producer, director), author, community activist, and fellow artist, I witnessed the growth of this community. I worked with an unusual cast of characters and discovered some seldom-discussed basics of a sustainable, stimulating arts/cultural system.

What follows is a personal narrative with perspectives drawn from my experiences with the art world and with Silicon Valley artists and arts institutions that stood apart from, challenged, or broadened, the mainstream perspective. Along the way, I hope to provoke timely and substantive questions and draw answers that elucidate what it means to build a vibrant arts community, such as the importance of small organizations in the cultural mix and of experimenting with open and flexible organizational structures. The Early Cultural Landscape

The road toward arts development in the South San Francisco Bay Area was paved by the San José Art League,3 formed in 1938 by a group of San José artists, mostly San José State University (SJSU) teachers and students, to stimulate public interest in art. In Depression-era Santa Clara Valley, the agricultural economy still functioned because of the blossoming of trees, the stone fruit that followed, and the diverse labor pool available. Post-WWII movements for civil rights in the 1950s and '60s laid the groundwork for change, opening doors in academia, community, and workplace, but change took longer to resonate in Santa Clara Valley, today better known as Silicon Valley. Conservatism accompanied Cold War fears and a local economy that increasingly stemmed from defense (Lockheed, FMC, Varian, later Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel). There were valiant attempts to open up the valley to new ideas. When post-WWII migration to California brought urban sprawl, the Art League sought to improve San José's downtown image and bring culture to the city center. Pioneers like art professor John De Vincenzi and artist Mary Parks Washington guided the Art League in the 1960s and '70s, went on to influence further art developments like the San José Museum of Art and their Black on Black Film Festival, and provided counsel during tumultuous times. The community branched out to found new museums, such as the Triton Museum in Santa Clara. De Vincenzi and Washington racked up decades of teaching, honors, and community service in the arts via multiple tacks, from the San José Fine Arts Commission to the San José Chapter of Links, Inc. The de Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University featured a permanent California history exhibition, including Native American art and art from Mission Santa Clara, plus changing contemporary art exhibitions. The de Saisset, in keeping with the university's culture of service, had a social justice component from the start, reaching out to diverse communities, including hiring women directors,4 when that was not the norm.

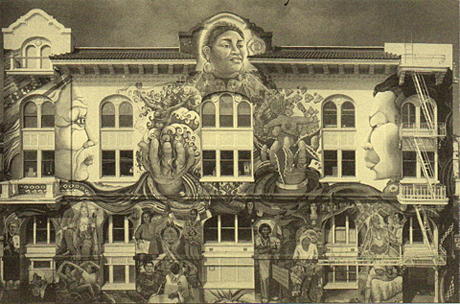

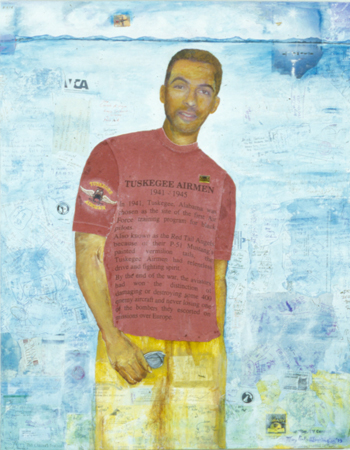

Mary Parks Washington, Erik, 1999. Mixed media, c 38"x30". Image courtesy Mary Emma Harris, Black Mountain College. A memorial tribute to her son, a screenwriter. Washington—artist, arts advocate, educator, historian—created "histcollages," embedding historic documents into her art. Her research shows artistry in the local African American community going back to the 1800s; a story of a janitor, a leading suffragist, and art stars from different centuries, three women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds; and the contemporary politics of art placement, substance, and importance in the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library and city spaces.

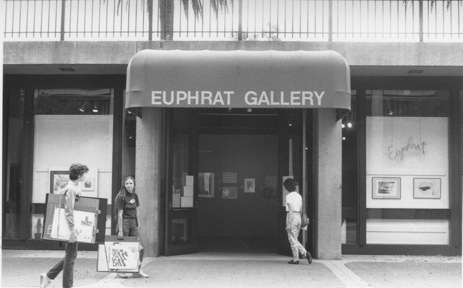

Despite these efforts, a sustained cultural blossoming has been difficult. Maintenance of routine practices with exclusionary results checked the momentum built on the groundwork of the 1960s. The newborn San José Museum of Art (SJMA) sought instant status and funding in the 1970s by emphasizing art history exhibitions, a common tactic using conventional groupings—artists abroad, Impressionism, Post-Modernism—rather than the diverse talents available here and elsewhere. Simultaneously, the San José State University (SJSU) art department, a white-male bastion closely aligned with the SJMA, banked on their 1960s legacy "School of San José," with its elegant objects, industrial techniques, and materials. Not surprisingly, for Stanford Museum of Art's 1974 Ten West Coast Artists, all ten artists selected were male. Even as late as 1986, when the SJSU galleries featured the School of San José exhibition for The First San José Biennial, of 23 participating artists, there were only one African American and one female represented. To make matters worse, in the 1970s and long afterward, people of means in the South Bay often went north for culture, even as our lingering orchards gave way to tract homes5 and de facto segregated communities.6 Considered a frill and scantily funded, the arts—in education and the community—encountered rough times, and many artists left the South Bay for San Francisco.7 For example, as a result of the enactment of Proposition 13 in 1978, funding for our fledgling Euphrat Museum of Art (then called Euphrat Gallery), founded in 1971 at De Anza College in Cupertino, was essentially cut to zero.8 Large arts organizations,9 often seen as the backbone of an arts community, had their own survival problems as they tried to cultivate individual donors and basic support from local government and the business community,10 but the loss of funding from tax revenue was particularly devastating to public arts education, social services, and community cultural programs. The 1970s: Pervasive Exclusion

The politics of inclusion in the arts was and continues to be contentious. Today, various kinds of discourse are taken for granted—how the arts might be used to advocate for human rights, social justice, and peaceful conflict resolution and promote cultural understanding and recognition; examinations of the function and place of art in the schools and our lives, or the relationship of art with government; the interaction of the arts with other academic disciplines. We had to fight to have those ideas taken seriously.

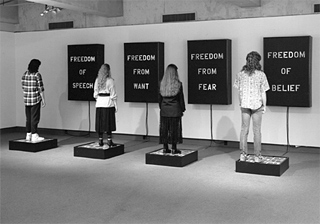

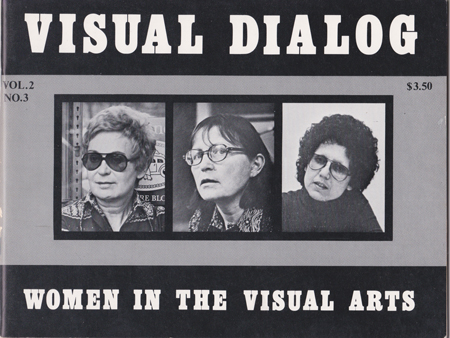

When I was a student in the 1970s, exclusion was pervasive—of women, people of color, people with disabilities, people considered "different" for whatever reason. There were essentially no women in art history survey texts used in universities. My first art history text was the 1973 version of H.W. Janson's History of Art: A Survey of the Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present Day, then the prevailing college text in the United States. It was a man's art history; no women were included, not even Impressionist Berthe Morisot or the legendary Georgia O'Keeffe. Much of the non-Western world was passed over or lumped into a section on "primitive art" and a nine-page postscript, "The Meeting of East and West." Contemporary non-European art scarcely merited a mention, with the exception of a dismissively judgmental paragraph about Expressionism in Mexico.11 It was a long road from the woman as nude model or male fantasy object to a fully realized woman as professional artist, academic, and/or cultural leader. SJSU art department alumnae remember "fanny pinching in the elevator back in the '70s. Wine and cigarettes were the bill of fare for critiques." There were some discussions,12 but the art world clearly needed a jolt and an overhaul. At SJSU, visiting professor Judith Bettelheim did shake things up. In my early years as the director of the Euphrat Museum of Art, she contributed to the Museum's first major publication (1981) with an essay about Leila McDonald and "women's hobby art," citing barrier-breaking art historian Lucy Lippard.13 In her magazine Visual Dialog,14 satiric printmaker/educator Roberta Loach of Los Altos published statistics quantifying the appalling discrimination against female artists. Not only did that resonate with my scientific training in basing theory upon measurable information, it made the case to others who need to see the numbers.15

Visual Dialog, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1977, the second of two issues on "Women in the Arts." Roberta Loach published, edited, and wrote for Visual Dialog, 1975–1980, a scholarly California journal of the visual arts.

Even though in the 1970s more women, people of color, and those with diverse gifts and backgrounds were hired in teaching and administration, the institutionalized culture then prevalent in academia, galleries, and museums did not truly value diversity of issues and ideas.16 Working within these organizations, one often paid a heavy price personally, politically, and economically for advocating openness and inclusion. Tokenism—hiring a single female or nonwhite person, or programming exhibitions encapsulating artists by gender or ethnicity to demonstrate the institution's commitment to diversity—reigned.17 The general climate in many university arts programs undercut initiatives for change. Art that had any sort of socially relevant content (different from the status quo) was disparaged as "political art," as opposed to "real art."

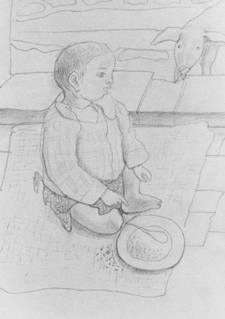

Pioneer artists Patricia Rodriguez and Marjorie Eaton with Rodriguez's heart sculpture in the exhibition Staying Visible, The Importance of Archives in 1981. Rodriguez, from San Francisco, described prevalent art world responses in the '70s: "[they] turned up their noses," "they didn't know how to accept my art," "it was difficult because I was not in step." She chose to do hearts instead of the usual abstract "yellow canvas with a white dot." Her art was cultural, emotional, as was Eaton's, and both had a passion for evocative murals. Eaton could have told Rodriguez about how it was painting with emotive artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in the 1930s, because she lived it. Eaton loved people. For many decades, Eaton nurtured a diverse avant-garde arts colony in the Palo Alto foothills on the historic ranch site of legendary Juana Briones and shared her legacy of caring. Contemporary academic research on Briones and Eaton is illuminating their times and their lasting meaning for California cultural development. Photo: Helen Fleming.

Breaking New Ground: Creative Strategies

The blossoming of Silicon Valley into a home for vibrant cultural startups was the result of three key growth factors: 1) The desire and courage to widen the vista and dialogue of new ideas and values begun by pioneering activists; 2) Formation of flexible, open structures that combine vision with a grounded understanding of real-world struggles that kept in touch with our basic humanity; and 3) Involvement of dedicated individuals, who provided counsel, advocacy, and investment of time and money. The combination of these attitudes and actions energized the breaking of new ground in addressing the issue of exclusion in the arts.

As a college instructor in studio art and art history, I was one of the change-seekers who rewrote studio and art history courses and books (late 1970s, early '80s),18 adding women and people of color, as well as unusual media and ideas. Some women altered their first names; others, including artist/activist/educator Ruth Tunstall Grant and me, occasionally used only our first initials to sidestep prejudice (for example, to get our work into an exhibition). But most exciting of all, we started to connect with others around the Bay. For me, as a motivated educator/presenter/activist, that meant learning from acclaimed visionary artists/activists, including Ruth Asawa, who developed whole-person art programs in San Francisco public schools starting in 1968 and her renowned Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in 1982; Patricia Rodriguez, founder of Las Mujeres Muralistas (women muralists), who created brightly colored murals in Balmy Alley and elsewhere in San Francisco's Mission District from 1970 to 1979; Carlos Villa, who directly challenged the entire academic/cultural establishment from within,19 organizing diverse, thought-provoking programs at San Francisco Art Institute; and then-novice artist Mildred Howard, Berkeley, who curated a Heartfelt Hearts exhibition in 1977 that included her own mixed-media textile constructions, Chocolate Hearts.20 Years later, Howard would be featured in top galleries, museums, and art history survey texts. Building New Forms

We began to build new forms of arts startups from scratch in the cities of the Peninsula and South Bay, gathering together a unique blend of people from the arts and academia, along with forward-thinking government and business leaders. Without the decades-long dedication of a broad base of partners and leaders, all the good that was accomplished would have taken much longer and been far more difficult than anyone could have possibly imagined. Our new hybrids included old-timers, newcomers, people finding their way in satellite cities, special-needs populations, supportive nonprofits, people from other parts of the world. Building community with a group of insightful, innovative dynamos proved to be the real energizer.

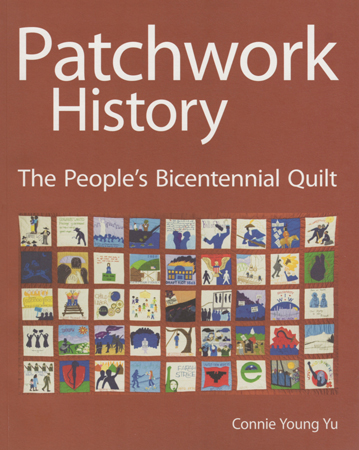

Two such dynamos were cartoonist Gen Pilgrim Guracar and historian Connie Young Yu, an amazing duo on the Peninsula who moved past barriers as early as the 1970s. They reached across cultures and disciplines, and brought together people from different walks of life. Using pen and paper, needle and thread, they combined living art and democracy. Guracar organized the dozens of women creating The People's Bicentennial Quilt (1974), and Yu wrote the book The People's Bicentennial Quilt: A Patchwork History (1976) that tells the story behind each square. At the Euphrat, we wrote about this early collaborative public art as part of our exhibition and publication The Power of Cloth: Political Quilts, 1845–1986.21

Patchwork History, The People's Bicentennial Quilt, Connie Young Yu. 1976 version printed by UP PRESS, East Palo Alto, CA. Republished by the Saratoga Historical Foundation in 2010.

"We made this quilt," wrote organizer Gen Guracar, "in answer to those who would commercialize our Bicentennial celebration … leaving us without a spiritual link to those who struggled so hard for the rights that we have now." In her foreword, Connie Young Yu writes: "We wanted to portray the people as making history: the nameless, countless members of movements and struggles that have affected the soul and character of America. We felt there was much in American history that could unite us and inspire us in a cynical time…We hope to inspire other community groups to celebrate American culture and history in a true revolutionary spirit." In the same time frame, Deanna Bartels (now Tisone), Betty Estersohn and Joan Valdes used video—then "cutting-edge" technology—to explore and document breadth in San Francisco Bay Area art making, even art and open space. The three Peninsula artists taped early social activists/environmentalists Frank and Joséphine Duveneck, who purchased and used their land, Hidden Villa in Los Altos Hills, in order to protect an entire watershed, advance social justice, and promote environmental education. The trio's Marjorie Eaton video opened a world of hidden Silicon Valley cultural histories from Ohlone Indian and local pioneer struggles in post-Mission days to a modern family-like community of artists. It inspired me to collaborate with them on an exhibition, publication, and further programming. The NEA-funded First Generation videos included visual art stars like Ruth Asawa, dancers Jasmine and Xavier Nash in the early '70s in the Fillmore, and clay artist Bea Wax in Palo Alto. First Generation was one of Tisone's many collaborative, interdisciplinary art projects over the last decades. Today we are working on making more of this history accessible and available online. Shoots and Offshoots

In the late 1970s in San José, a group of aspiring curators with a strong SJSU contingent began a series of attempts to create viable spaces where emerging artists could show their work. Art professor Tony May and I first wielded hammers for art in an old building on Santa Clara Street in downtown San José. May was, and continues to be, a key catalyst.22 We put our energies into Works Gallery (1977), an offshoot of Wordworks, which in mid–1980 reopened as the San José Institute of Contemporary Art (SJICA). Works Gallery, SJICA, and others could be termed alternative art spaces, art lingo for increased non-traditional exhibition opportunities for emerging artists. Because artists, poets, and other creative people need multiple venues to flourish, the creation of these alternative organizations sparked cultural growth in Silicon Valley and put the area on the arts map.23The core groups I speak of here, however, might be called "alternative-alternative" organizations. These smaller organizations (and offshoots from large organizations that manage to grow independently from their parent group) often begin with altruistic goals and a commitment to community-building, and are free to exhibit more flexibility. Pioneers in this arena, like artist Ruth Tunstall Grant, led the way and overcame obstacles. Tunstall Grant gave SJMA and Silicon Valley new dimensions by drawing in community diversity, giving opportunities to creative people of color, and starting studio art programs in city schools and the county youth shelter.24 The alternative-alternative groups have often served as reality checks, providing grounding for the large institutions. These shoots and offshoots find new doors to open, notice diversity of ideas in their own backyard, meet needs of diverse artists and the student in all of us, and understand the social dynamics and issues of their communities.25 Opening the Door

During the late 1960s and continuing into the '70s and early '80s, various small organizations—hybrids of business, education, and volunteer models, supported at times with government funding—opened doors to other cultures. I grew to know and value their work, and collaborated extensively with some of these innovators. In 1968, two visionaries, artist/educator Cozetta Gray Guinn and her physicist husband Isaac "Ike" Guinn, established Nbari Art, a museum-quality gallery in Los Altos, highlighting the work of students at Stanford and UC Berkeley. Their gracious and welcoming shop featured imported African art and African American art, and offered us an invaluable cultural resource for four decades. In the early 1970s in an abandoned downtown San José storefront near First and San Carlos Streets, artist Mary Jane Solis26 and activist Adrian Vargas (founder/director of San José's Teatro de la Gente, 1967–1977) co-founded El Centro Cultural de la Gente, the South Bay's first Chicano/Latino cultural center. El Centro's exhibitions, art programs, and luminaries had an impressive roster, including: Lorna Dee Cervantes and her Mango Press, artist José Antonio Burciaga, Las Mujeres Muralistas, and Luis Valdez, the father of Chicano theater. Solis curated art exhibitions, managed arts programs, called attention to social justice related art, and spoke out for multicultural arts—for "a place to come together and feed the spirit." In 1973, renowned painter Paul Pei-Jen Hau (Hau Bei Ren) and Mary Hau opened their Chinese Fine Arts Gallery in downtown Los Altos. Their personal invitation to understand Chinese culture countered lingering anti-Chinese sentiment, and in 1979, with Paul Pei-Jen Hau as its guiding spirit, artists, and friends founded the American Society for the Advancement of Chinese Arts.27

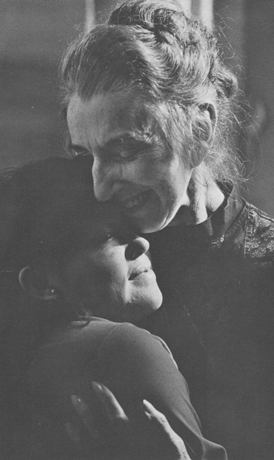

Paul Pei-Jen Hau (born in 1917) and Mary Hau in 2009, celebrating at the reception for Looking Back, Looking Ahead.

Artist Terese May remarkably opened the stubborn art world door to the culture of domesticity, through her quilts and paintings. Periodically, she assisted the San José Museum of Quilts & Textiles, the first museum in the U.S. to focus exclusively on quilts and textiles as an art form. Started in Los Altos in 1977, the museum was essentially a collaborative, volunteer organization for a decade before hiring its first paid director. In 1981 in Palo Alto, Trudy Myrrh Reagan started YLEM: Artists Using Science and Technology.28 With our similar backgrounds in science and art, Reagan and I exchanged ideas and collaborated on exhibitions. In 1984 at SJSU, quiet-but-determined art professor Marcia Chamberlain took the initial lead of CADRE Laboratory for New Media, an interdisciplinary academic and research program dedicated to the experimental use of information technology and art.29 We strategized frequently, and she invited me to write the essay for the CADRE '84 catalog. Expanding the Boundaries

While doors were opened, the struggle to change minds continued. Quilts, fiber arts, and "computer art" were saddled with countering prejudices about "women's work" or "right/left brain" thinking, and had little acceptance in the academic and institutional art world. In fact, the two worlds rarely communicated.30

In 1979, when I became director/curator at the Euphrat Museum of Art at De Anza College, I brainstormed with activists and potential staff and board members how we could build community, foster civic engagement, and go beyond disciplines and narrow definitions to explore new ideas. For us, the open-door policies of the community college system and the logic of partnerships were great avenues for experimentation. We realized the urgent need for new systems to open up opportunities, give visibility to contemporary artists and ideas from diverse sources, and promote thought and discussion. With this in mind, we initiated a unique campus/community partnership.31 Working with incredible innovators, beginning with artists/activists Jo Hanson (Art from Street Trash) and Carlos Villa (performance art with dramatic installations of feathered capes) and poet George Barlow, we expanded the boundaries of what could be considered art and what merited attention or discourse, and began a stellar poetry series that would include Dennis Brutus and Quincy Troupe. Early exhibition examples were The Workplace/The Refuge (Janet Burdick and Scott Miller recreating their San José studio in the Euphrat) and Men and Children (views from six Bay Area male artists with diverse backgrounds) in 1980; an exhibition to celebrate the 1981 International Year of Disabled Persons, developed with De Anza's Physically Limited Program; followed by our seminal Staying Visible, The Importance of Archives, which directly addressed visibility issues. CROSSOVER, the first of many art and technology exhibitions, came in 1982, and Commercial Illustrators, 1981, and Illustration/Design, 1983, introduced processes and artwork from Bay Area commercial artists, another discipline not recognized at that time by the art world.32 And that was just the beginning.33 We responded to suggestions from the community. A student asked me why there never seemed to be any religious art in modern art galleries. So in 1982, we investigated the subject in Art, Religion, Spirituality.343536

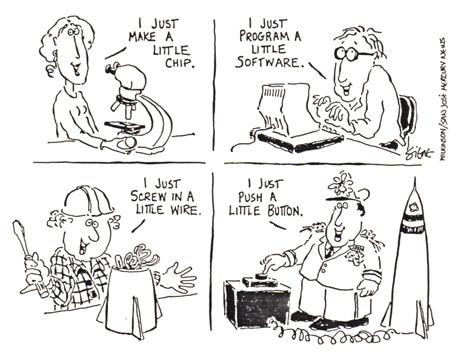

Signe Wilkinson, 6/23/82, San José Mercury News, reprinted in Illustration, Design. Commercial art was not recognized by the art world in the early '80s. To broaden the institutional mindset and see larger contexts to struggles, we worked with people in related fields such as Wilkinson. A cartoonist extraordinaire who got her start sitting in on San José Mercury News editorial sessions, Wilkinson went on to Philadelphia and became the first woman to win a Pulitzer in cartooning. Feisty and funny, she could open anyone's mind.

There were noticeable structural parallels between the growth of the alternative arts scene and that of Silicon Valley tech culture, although tech culture has had its own problems with insularity. From Hewlett Packard in its early days to Google, many companies saw the wisdom of loosening reins and regulations, and were increasingly open to new values, different cultures, and varied schedules and ways of working. Dress codes relaxed from the stiff suits of previous eras. Size played a role in cultural development. Large companies gave rise to spin-offs, and startups were staffed by even smaller teams. Via these spin-offs and startups, innovative individuals could make direct connections with education, youth, music, and gamers, as well as counterculture, geek and activist cultures, and the global community. Steve Jobs started Apple Computer in Cupertino in 1976, just down the street from the Euphrat. Apple supported and participated in many early Euphrat Museum exhibitions, and the Euphrat created art exhibitions in numerous Apple buildings. We connected with Apple on many levels.37 The Late 1980s/1990s: New Ventures, Ethnic Dimensions, Community Building

At Stanford, Cecilia and José Antonio Burciaga did something different. From 1985–1994, the couple lived at Casa Zapata as Resident Fellows—she as a top university administrator, he as resident artist—both working closely with student and community needs.38 José (a.k.a. Tony, Toñ o) created murals at Casa Zapata, and used comedy to attack racism and narrow divisive thinking, and published poetry and writings, e.g. Weedee Peepo (1988). ("…Tony remembers his parents preparing for their citizenship tests and saying to each other: 'Have you learned el Weedee Peepo?' That was how the Burciagas pronounced the words that perhaps more than anything else make American, Americans: 'We the People,' the first three words of the preamble to the Constitution." José Cardenás, Arizona Republic, 2005.)

José Antonio Burciaga taught us how to Drink Cultura. Drink Cultura was first published in 1979 by Lorna Dee Cervantes's Mango Press in San José. Detail of T-shirt accompanying the publication.

In 1989, artists/activists Betty Kano of Berkeley and Flo Oy Wong of Sunnyvale founded the Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA) in the Bay Area to "promote the visibility of Asian American women artists" who lacked recognition in their own traditional culture and were again overlooked when national museums sought Asian art stars. Also in 1989, Maribel Alvarez, Rick Sajor, and Eva Terrazas envisioned arts programming as a vehicle for civic dialogue and social equity and founded Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA) in downtown San José. Alvarez recalls, "When we got involved, the way to ignite the sort of movement included in our name…was a literary movement." We both worked with another powerful arts couple, poets Juan Felipe Herrera and Margarita Luna Robles. They organized poetry readings downtown, in East San José, and at the Euphrat Museum in the 1980s, lifting us all in spirit, bringing poems by, from and for the people, without shrinking from telling hard truths in poems like Robles's Suicide in the Barrio. I marveled at the ongoing vibrancy of Ruth Tunstall Grant, who in the 1990s founded Genesis/A Sanctuary for the Arts in San José creating exhibitions, presentations, performing arts, and artist studios, bringing together different cultures and simultaneously establishing a visible presence for the black community. Somehow, in the same decade, she developed the art program for foster youth at the Santa Clara County Children's Shelter, after directing and building the outstanding children's art school at SJMA in the 1980s. After she worked in San José, artist Jean La Marr introduced us to Urban Indian Girls, which became part of Euphrat's 1984 FACES exhibition; a decade later La Marr collaborated with the local Muwekma Ohlone Tribe to create The Ohlone Journey mural in Berkeley. Given the Native American Diaspora, my early knowledge of local Indian art often came through transient artists who connected both with far-flung traditional communities and part-time academic assignments around Northern California.39 As artist Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, Cupertino, put in an artist statement: "With beauty, grace, and traditional form, my work expresses the quiet rage that has permeated indigenous peoples of the Americas for over five hundred years."40 Underwood would develop and head the textiles/fiber program at SJSU for over twenty years.

Jean La Marr, Urban Indian Girls, 1981. Etching, 16"x18".

The above are just part of the story. There has long been arts activity beyond nonprofits. In her 2005 book There's Nothing Informal about It: Participatory Arts Within the Cultural Ecology of Silicon Valley,41 published by Cultural Initiatives Silicon Valley, Maribel Alvarez chronicled amateur, folk, commercial, and avocational arts.42 In the new millennium, Silicon Valley's cultural ecology was changing rapidly with immigration: the white population became a minority, displaced by a massive population of emigrants from India, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Mexico.43 At the same time, new systemic disparities in formal education and income levels would increasingly present both opportunities and challenges in social, economic, technological, and government realms. At a forward-looking event in 199544 at the Euphrat, the Arts Council under new director Bruce Davis applauded the "arts as an intervention for social ills,"45 connecting arts with government, schools, youth, veterans, social services, and prisons. Presenters included a county supervisor, a judge, and arts/community leaders from Menlo Park and East Palo Alto to Gilroy. "We had to run two sessions!" Davis recalled. Counsel, Advocacy, Support

What kept innovators going even in the face of personal attacks, political maneuverings, and endless barriers put in their paths by resistant administrators, colleagues and institutions? This brings me back to Consuelo Santos-Killins. Ruth Tunstall Grant and I both sought seasoned perspectives from Santos-Killins. She possessed insight and understood the unique value of new ventures. As she battled cancer for five years, Santos-Killins continued her wide-ranging activism, firing off letters to top policymakers. Grant and I, like many other arts advocates, faced incredible struggles. Grant: "One gets beat up. You think you know the answers; but after a while, you are not sure anymore." Even on our worst days and hers, Santos-Killins could be counted on. Good advice and support were gifts she brought to so many who struggled to build the arts and art education systems we have today.

Advocacy was another gift of Santos-Killins. Advocacy, little heralded or discussed, is a well-worn term with levels of meaning. The advocacy I laud and refer to here includes speaking up for people, ideas, and/or organizations in a public letter or at a public meeting.46 None of the blossoming could have happened without supporters, from a key trustee to a bold city councilmember or a few visionary county and state policymakers like Santos-Killins, to donors, board members, students, volunteers, brainstormers, barnstormers, activists, collectors, companies, and educators in other disciplines with fresh perspectives.47

Protect the Child, Ruth Tunstall Grant, c. 2004. Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 5'x8'. From the series entitled, Breaking the Chain of Abuse. An enlarged reproduction became a section of the Japantown Mural Project (2012-2013), a community project by rasteroids design and the City of San José Public Art Program to celebrate an historic San José neighborhood. Art by 50 local artists, more than 60 large panels of color, covered chain-link fencing surrounding barren land, once San José's maintenance yard, and 100 years ago, one of San José's first Chinatown settlements known as "Heinlenville."

The New Millennium: Business, Democracy, Change

Today, our traditional cultural, educational, and media institutions, so important to our democracy, are challenged by new technologies and a changing economy that demand new business models. Daily newspapers search for successful ways to develop and monetize their online product. Educational and cultural institutions participate in online and other technological changes, adapting through private funding and unusual collaborations. As we sort out what is gained or lost,48 we have examples of new "alternative-alternative" organizations forging the trail, such as Silicon Valley De-Bug, with whom I worked often. This media, community-organizing, and entrepreneurial collective coordinated by Raj Jayadev has an expanded reading of art, information, and democracy as its basis.49

Abraham Menor, The Art Of War, 2009. Digital print. B-boys (breakdancers) presenting their skills at San José's largest b-boy/b-girl event. Menor has worked with Silicon Valley De-Bug and photographed a hidden Silicon Valley for years.

An open door in the arts plays an ongoing role in democracy; this is even more important today as we see exclusion continue in many ways. In News in a New America (2005), Sally Lehrman of Santa Clara University describes the "invisibility" of people and ideas in journalism and new media, emphasizing how access to information about each other is essential for our democracy. It is this same communication that is at the core of the arts. However, many people do not think of arts organizations and institutions as being essential for our democracy. "Invisibility" of people and ideas in the arts precludes exchange of information about each other. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston reminded us of that recently in The Manzanar Lesson: Telling our stories strengthens democracy50 in which she urges people to tell their stories, experiences, and perspectives because "democracy depends on it."51 In 2004, Euphrat Museum spotlighted Titus Kaphar's Visual Quotations series,52 drawn from classical paintings illustrating one version of the founding of our country. Kaphar only painted the African American(s); the rest of the scene is white, leaving a disjointed figure(s). Kaphar wanted viewers to consider the individual represented, to see "a people of dignity and strength, whose survival is nothing less than miraculous," bringing the visibility issue to light. Have things changed in Silicon Valley's contemporary arts environment? Yes and no.53 We can see a lasting breakthrough in MACLA, which has an inclusive community vision that has brought dimension to South First Street in San José. Technology-oriented ZER01 and its Garage, and the San José Museum of Quilts and Textiles have become crucial anchors for the SoFA District arts community. Silicon Valley De-Bug boldly plows new ground. More Work to be Done

Some 50-plus years from the March on Washington for jobs and justice, so much community-building work remains. Does discussion about an "open arts community" really exist in our local academic world and cultural institutions? Much of Silicon Valley academia has dropped the ball in terms of providing a center for cohesive, open discussion, let alone a base for support, in part because funding cuts have exacerbated academic departments' territorial tendency to focus on their own bread-and-butter programs. Thus art departments tend to be insular, with other fields—women's, gender, and cultural studies, humanities, or other social and physical sciences—filling in where needed. Our local cultural institutions suffer from similar problems and financial vulnerability.

Moreover, even institutions grown in opposition to exclusion can, by defining themselves narrowly or through unconscious prejudicial behaviors, continue exclusion by class, educational level, discipline, or background. It is so easy to separate ourselves. In terms of visibility and participation, clearly more work needs to be done—with arts at the table—across all sectors, including with at-risk youth populations, low-income neighborhoods, threatened environments, out-of-whack justice systems, and out-of-balance boardrooms focused only on a myopic bottom line. It remains difficult to develop or discuss the region's integrated art history within its ongoing context. Recognition provided through random, selective awards and obituaries typically fails to provide a coherent, integrated appreciation or understanding. One local artist labels the drag on any art scene as "selfishness, contentment, lack of desire to do the hard work." I have suggested that we take action to extend and document the arts forum across cultures, disciplines, and sectors and include the role of arts roots, startups, and offshoots. In order to do this, we need a local archive or a locus of discussion, yet no central historical record is available online. Advancing previous cross-disciplinary and cross-sector initiatives without a clear place to start an examination of past efforts is especially challenging. We need ongoing attention to build on the contributions of our diverse forerunners. Too often websites are not archived and disappear. Cultural Initiatives Silicon Valley, Nbari Art, and Arts Council Silicon Valley (ACSV) sites no longer exist. Major institutions like ACSV (now Silicon Valley Creates, 2013) and SJMA have not given web attention and context to pioneers and change agents like Ruth Tunstall Grant. One option could be a multi-year, interdisciplinary campus and/or community project, with an annual published essay related to the meaning or practice of "the spectrum of the arts in Silicon Valley." Such a project would open doors, collaborate across disciplines and sectors, and connect side history with mainstream history. An accessible, ongoing web presence would be an essential element, combined with the involvement of students doing related research, documentation, and projects (including drama or other arts forms) on individuals, organizations, and/or concepts. Gathering and Flourishing

Juan Felipe Herrera, our California Poet Laureate, performed his poetry on April 4, 2012 at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, accompanied by jazz musicians. "Good words. Good hearts," he said. His poem, Let Us Gather in a Flourishing Way, speaks to us all. "Let us gather in a flourishing way… Let us gather in a flourishing way," he intoned with the drums. Ruth Tunstall Grant nodded when I mentioned the glowing experience to her. "Flourishing. One has no idea what will grow. But it needs to be face-to-face, not Facebook," she said.

Let us, then, learn from the various elders and all those who have worked "in a flourishing way." Face-to-face conversations and stories are the start of an ongoing gathering of the thoughts and experiences of some of our artists/activists who have contributed creatively to the blossoming of Silicon Valley. I have introduced some of them, presented a context of Silicon Valley community building, raised questions, and suggested actions for research, documentation, and discussion. But this essay is just the beginning. I invite you, the reader, to offer your perspective and to fill in the blanks in an appendix, available later on www.janrindfleisch.com, so we can recognize and give context to more key artists, organizations, and others who opened up new doors. Knowledge of the past will inform our dialogue as we move forward. Let us build upon their experiences to create a truly vibrant arts community in Silicon Valley. FOR FURTHER READING

San José Art History to 1985

Artist/educator Roberta Loach, Los Altos, published the quarterly magazine Visual Dialog, from 1975 to 1980, with essays, interviews, reviews and columns, expanding women's role in connecting Silicon Valley arts with Bay Area and national arts and arts activism. In 1979 and 1987, artist/professor Marcia Chamberlain published the Irregular Gazette, "a once in a while publication of the SJSU Art Department," an opportunity to think about and understand women's contributions, cultural diversity, and entrepreneurship. 1987 articles brought forward emerging artists, the art and humanism of Dorothy Liebes, and the future for CADRE Laboratory, fiber, and foundry programs. The ambitious A Celebration of 100 Years of the Department of Art, 2013, Natalie and James Thompson Art Gallery, refocuses on the SJSU art department's past to "tie to larger cultural and social movements" of today, but creates a sense of a more diverse and diversity-welcoming past academic cultural climate than existed. Importance of Archives For understanding the making of art history and the times, including local activism, see Staying Visible, The Importance of Archives, Jan Rindfleisch, 1981, exhibition publication, Euphrat Museum of Art. Foreword by Paul Karlstrom, West Coast Area Director, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Commentaries included Michael Bell, Registrar/Cataloguer, Oakland Museum of California. Eleven articles involved researchers from various institutions concentrating on individual artists, all women, with a focus on putting material into archives. Karlstrom, Bell, and others brought project insight, guidance, and support, particularly important in our early critical days of discovery.

This essay would not have been possible without discussions and insight from Nancy Hom, Ruth Tunstall Grant, Judy Goddess, Laurel Bossen, Lucy Cain Sargeant, and Tom Izu, with additional assistance from Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, Mary Parks Washington, Gen Pilgrim Guracar and Connie Young Yu, Ann Sherman, Bruce Davis, John Kreidler, Michael Bell, Thomas Rindfleisch, Janet Burdick, Samson Wong, and many artists and activists mentioned in this essay, and unmentioned, with whom I spoke.

1In addition to arts organizations, including San José Symphony, Pacific Peoples Theater, and Institute for Arts and Letters at San José State University, Santos-Killins served two antipoverty agencies, as well as the Santa Clara County Mental Health Association and Friends of Guadalupe River Park. 2

The local contemporary art scene was then anchored by the academic/exhibiting centers of Santa Clara University, Stanford University, and San José State University (SJSU), augmented by the new community colleges, and by art associations, centers, leagues, guilds, societies, estates, and clubs usually of a regional nature, such as Los Gatos Art Association, or related to a specific arts medium. 3

In 1875, The Art Association, as it was then named, was formed in San José, with their first exhibition in 1876 at the Normal School (now SJSU). 4

First de Saisset Director Joséph J. Pociask, S.J. (1955–1967), in 1958 presented a prescient solo exhibition of Paul Hau, who had recently arrived from China and was teaching at the Pacific Art League in Palo Alto, then known as the Palo Alto Art Club. Directors Brigid Barton (1978–1984) and Georgiana Lagoria (1984–1986) gave early opportunities and critical exposure to women. Santa Clara University, a Jesuit institution, and the de Saisset Museum, which includes both art and history components, have been in a unique position to join arts, interdisciplinary and social justice programming, and discussion of values and ethics. 5  Carol Marschner Malone, Grant Road Mountain View. Marschner Malone has drawn/painted our evolving Silicon Valley; in the '80s, she chronicled old Cali & Bro. on Stevens Creek Boulevard, the Olson Orchard in Sunnyvale, St. Leo's Church in San José, guys playing Pac-Man. 6

The ethnic distribution in Santa Clara Valley during the 1970s could be generalized as follows: an overwhelmingly white population (94% in 1970); a small black population (in contrast to 61% in neighboring East Palo Alto in 1970); a sizable Latino population in areas of Mountain View, Sunnyvale, Santa Clara, and San José; and a small, fast-growing Asian population scattered.

7

Mountain View's Community School for Music and Arts began in 1968 with volunteer teachers; their first art education contracts with the Mountain View School District came in 1981. Support for the arts was so low in Cupertino that, in a budget crunch, high school art teachers told me administration wanted to let some of them go and have physical education teachers teach their art classes. 8

De Anza College's Euphrat Museum for years faced the constant threat of having its already truncated space turned into a computer lab. Before my directorship, in 1978, Proposition 13 resulted in the elimination of funding for the Euphrat, which had been supported by Community Services; about two-thirds of the original museum had already been converted to classroom space.

9

The major arts organizations included Stanford Museum of Art (established 1891, reopened in 1999 as Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts after completion of revival begun in 1963), Montalvo Center for the Arts (1939), de Saisset Museum (1955), Triton Museum of Art (1965), and San José Museum of Art (1969 in former city library, 1991 new wing). 10

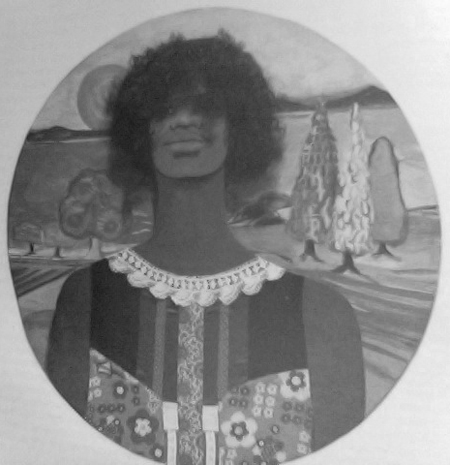

During my term as Euphrat director, I crossed paths with two San José mayors who stood out as supporters of the San José Museum of Art and of the arts in general: Janet Gray Hayes (1975–1982) and Susan Hammer (1991–1999). While Hammer built a solid arts support record and inspired a 10-year cultural plan for Silicon Valley, she also personally connected with local artists and collected their work.  Marie Johnson Calloway, Sun Circle. Mixed media, 3' diameter. Collection of Mayor Susan Hammer. Photo: Helen Fleming. 11

The Janson text (1973 edition) said José Clemente Orozco and "a group of young painters" in Mexico in the 1920s and '30s, inspired by the Mexican Revolution, often overburdened their works with ideological significance. Orozco was identified as the artist "least subject to this imbalance." The text made no mention of iconic artists Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera, who would have lasting international impact, he with provocative murals, she with piercing self-portraits. 12

Most of us were aware of artist/activist Judy Chicago (Through The Flower, 1975; premiere of Dinner Party, 1979, at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) and, to a lesser extent, of artist/activist Carlos Villa (Other Sources, 1976, San Francisco Art Institute, symposium, events, publication, exhibitions of artists working on the "shadow side" and margins of the mainstream Bay Area art world).

13

Art historian Lucy R. Lippard inspired many of us, e.g. with From the Center, 1976. Bettelheim referenced Lippard's "Making Something from Nothing (Toward a Definition of Women's Hobby Art)," in Heresies, Winter 1978. Lippard described how women look at the objects in their physical environment and use them for their own creative goals. Bettelheim's dissertation on Caribbean street masquerades and her training in African art history also led her to greater understanding of the vast scope of art in our country.

14

"Does Sex Discrimination Exist in the Visual Arts?" Eleanor Dickinson and Roberta Loach, Visual Dialog, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1975-76. The U.S. box scores at the time for numbers of men (M) and women (F): group invitationals—M 1324, F 699; one-person shows—M 1421, F 38; Oakland Museum collection—M 413, F 119. Females made up 75 percent of students in U.S. art schools in 1971. Other statistics Dickinson and Loach researched and reported compared degrees, faculty, reviews, acquisitions, and gallery representation.

15

The marginalizing of "women artists" encouraged aberrant behaviors. Some women ignored or laughed off demeaning male behaviors, sexual innuendo, trivializing of ideas. Some fought back.

In the mid 1970s, a local sculptor and university arts professor exhibited a college art gallery full of his nude female bronzes, shown bound and gagged, prostrate and laid out. The academic gallery context offered the students elevated interpretations. Instead of accepting them, a Silicon Valley cartoonist Gen Guracar created a cartoon panel about standing up to such demeaning content. In the first cell, the male artist is shown sculpting a bound woman. But in subsequent cells, the female sculpture comes to life, jumps up full of anger, throws off the bindings and mouth gag, grabs the hammer and chisel, and chases the sculptor out of the studio. I saw the cartoon years later and applauded the cartoonist's spunk, but my basic question at the time was: What are we teaching?

For the arts to function in support of community and democracy, one needs freedom of expression and an educated populace, not rebuked and marginalized citizens.

16

Many experienced ongoing exclusion. In 1985, writing The First San José Biennial essay for SJMA, I noted the minimal ethnic representation overall. The biennial exhibitions did not give a sense of our ethnic mix nor in any way reflect the unique experiences of major portions of our population.

Overall, progress came with visionaries like Helen Jones, dynamic from her wheelchair. In 1980, Jones, head of De Anza's Physically Limited Program, proposed the exhibition To Deny the Right of Any Person is to Deny Our Own Humanity, revolving around related art and needs. For context, Oakland's Creative Growth, the oldest and largest art studio in the world for people with disabilities, only began in 1974.

Exclusion in the early 1970s extended to veering from the mainstream. Web designer Marte Thompson reminded me of Bill Martin, the legendary visionary artist who taught at SJSU in 1973-74, and Michael Whelan, a student there at the same time, who became a celebrated science fiction book cover illustrator. "In those years, representational painting was frowned upon by mainstream art, and these artists, and any instructors, notably Maynard Stewart and Dr. Raymond Brose, were ostracized for their insistence on teaching what is now called 'classical realism.'"

17

The large organizations' advances were often limited to Women's History Month or Black History Month. Topping the social/economic/academic hierarchies of collecting and validation, these institutions emphasized established artists and were often quite removed from basic life experiences of most artists.

Inclusion is not a simple matter of numbers or demographics or just working with the community you have, regardless of makeup. The question/crux is how we see ourselves in the world, how we understand underlying racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression, and what that means to us as individuals, a people, and a country.

18

Not long after, books like Women Artists: Recognition and Reappraisal from the Early Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century, Karen Peterson and J.J. Wilson, 1976, were published. The descriptive title highlights a long-standing conundrum; we are not "women artists" but artists. The same issue is raised by Black Artists on Art, Samella S. Lewis and Ruth Waddy, 1970. (Lewis founded the Museum of African American Art in Los Angeles in 1976.) 19

Villa (1936-2013) for decades developed diverse, thought-provoking programs at San Francisco Art Institute, nurtured students, connected with other artists and activists on a broad scale, and challenged the mainstream art world through exhibitions, conferences, and symposia.

20

Chocolate Hearts at Berkeley's Fiberworks (founded 1973) consisted of candy boxes where each "chocolate" was a portrait of a family member or ancestor, presenting black experience and history seldom seen in a "mainstream" art gallery. Howard and I reconnected in 2011 when she created a Blue Bottle House temporary public artwork in front of Palo Alto City Hall, almost a stone's throw from where three decades earlier we had visited the small international art colony of painter/actress Marjorie Eaton. 21

The Power of Cloth: Political Quilts, 1845–1986, was based on the national research of two other Silicon Valley quilt enthusiasts, Jane Benson and Nancy Olsen. The exhibition included an unknown artist's Underground Railroad quilt, c. 1860, supporting the abolitionist cause, and contemporary artist Faith Ringgold's The Purple Quilt, inspired by author Alice Walker. 22

Artist Tony May taught an Art in the Community class at SJSU for decades and created collaborative public art projects, such as a large umbrella memorial to San José community activist and spiritual leader Father Mateo Sheedy. May gave a group of us a ceramic fish from his temporary public installation Milagro de los Pescados. Many of May's students brought new dimensions to art and community. Hawaii-based artist Lonny Tomono, schooled in Shinto temple restoration in Japan, collaborated on a spiritual tree house with May. Artist Margaret Stainer developed the Ohlone College gallery in Fremont over three decades; she researched part of our Staying Visible publication, 1981. Valerie Patton, who went on to teach in the prisons, commented: he [Tony] could "get [us] past the pomp and circumstance of art to genuinely and spontaneously respond to ideas … a subversive force within the college art department … offer[ing] the alternative of an exploration of conceptual art…. Some of [the] temporary artworks produced collectively by students (and other collaborators) were this artist's best legacy of all." 23

"Art Wars" T-shirts memorialized the late '70s conflicts and growing pains. Works/San José and some others have good basic organizational histories on their websites.

24

Artist Ruth Tunstall Grant served on the first boards of Works and the Arts Council of Santa Clara County. She spearheaded Hands on the Arts, a multicultural arts festival that became Sunnyvale's signature event, soon going on its 30th year. She pioneered the San José Museum of Art studio art programs in city schools in the mid 1980s and wrote a winning grant for the seed money. Convincing the museum director to start this amazing outreach program to impoverished areas was not an easy sell for Tunstall Grant. She was uniquely able to develop unusual new programs and offshoots within the mainstream system, and also to start an arts nonprofit from scratch.

25

On national and state levels, various government programs utilized artists and gave them a taste for public service. Those with local impact included the federal CETA program employing artists in hospitals, prisons, and other public service (1973–1982), and California Arts-in-Corrections in the state prisons (1982-2003). The latter began in the '70s as the vision of Eloise Smith, the first California Arts Council Director, and her spouse Page Smith, founding provost of Cowell College at University of California Santa Cruz and activist for the homeless in Santa Cruz. 26

Solis helped found MACLA (Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana) in 1989, and chaired Multicultural Arts Development, 1987-95, when on the San José Arts Commission. At the Santa Clara County Office of Human Relations (OHR) since 1997, she has been in charge of Community Relations and the Commission on the Status of Women; has created community projects that combine arts, culture, and human rights; and, with OHR and Human Relations Awards, has publicly honored similarly minded individuals and organizations. 27

In the coming decades, Hau would become very popular with an influx of Chinese into Silicon Valley who know and buy his work. But Hau's personal reach was always cross-cultural. Only two of the first ASACA members were Chinese. Connie Young Yu highlighted Hau in her 1986 book Profiles in Excellence: Peninsula Chinese Americans, published by the Stanford Chinese Club (1965) for their 20th anniversary. She did not gloss over how unfriendly some Palo Alto residents who did not want to have a Chinese family as neighbors were to Hau. 28

YLEM explores the intersection of the arts and sciences and considers the impact of science and technology on society. YLEM grew in part from the Graphics Gatherings spinoff from the Homebrew Computer Club at Stanford, but with broader reach, and exposed artists and public to research work through public forums, exhibitions, and field trips. 29

SJSU Professor of Art Marcia Chamberlain initiated the CADRE Project (Computers in Art, Design, Research, and Education) and served as first Project Director for the CADRE 1984 conference, papers, and publication. With eight satellite exhibitions, numerous YLEM members participated.  CADRE 84 cover. Logo design by Mary Sievert. Chamberlain also instituted SJSU's fiber arts program. Joel A. Slayton became CADRE director in 1988, and I would work with him again after he went on to direct ZERO1, the Art and Technology Network, founded in 2000. 30

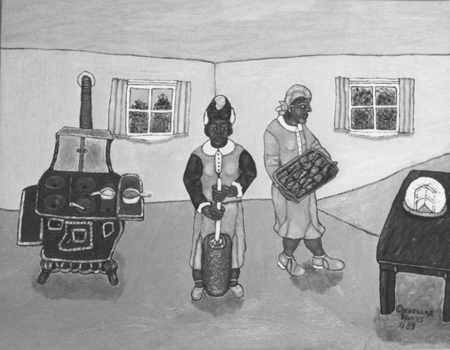

For women, support would come from maverick female art historians, like Moira Roth at Mills College; from Stanford's Center for Research on Women (later name changes), which would also collaborate on the early Djerassi Resident Artists Program (1979) in Woodside; and cross-disciplinary campus groups that organized women's history months. Cultural support would come from campus departments, such as Intercultural Studies and a range of social sciences and language arts, along with historical societies, sororities like Links Inc., churches, and community organizations like Mid-Peninsula YWCA in Palo Alto.  Huellar Banks, Milk Churning, 1988. Oil on canvas, 22"x27". For over 30 years, artist Banks, an East Palo Alto resident, painted childhood remembrances after spending her days cleaning houses. Her art was recognized by the Mid-Peninsula YWCA and Stanford's Institute for Research on Women and Gender. Community activists were supportive in general. Science- and technology-related arts were often orphans, but had energetic core supporters in specific areas. Early computer graphics were highlighted in the '80s by Bay Area ACM/SIGGRAPH, a local chapter of the Association of Computing Machinery/Special Interest Group for Graphics. A former Stanford research scientist, Penny Nii spanned two worlds in her 1986 Building Blocks quilt to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the field of Artificial Intelligence; created the Penny Nii Art Quilt Gallery in Mountain View and curated an exhibition at NASA Ames in the 1990s; then delved into book art   Nii's Totality (left), 2001, led to Totality (right), 2012, a Digital Over Analog (D/A) book Nii created with Mohammed Allababidi and Enrique Godivia, game animators and app developers. D/A books "straddle the world of the book (analog) and e-readers (digital)." 31

The Euphrat was founded as the Helen Euphrat Gallery in 1971 by way of a bequest and the vision of E.F. and Helen Euphrat. In 1978, as a result of Proposition 13, funding was cut to essentially zero. We began building the unique college/community partnership with a forum concept around 1980. With the expertise of art historian Patricia Albers, then director of special programs, we became the Euphrat Museum of Art in 1992. Given the meager and spotty remuneration, we would never have survived and succeeded in the early 1980s without the creativity of artist Kim Bielejec Sanzo, assistant to the director, and support from district trustees Franklin Johnson, Dr. Gerald Besson, and Dr. Raymond F. Bacchetti, the latter two serving on the first Euphrat board. The Euphrat board would grow, champion innovation and help build programs, outreach, and the new museum building, most unusual for a community college. 32

We worked on exhibitions and publications with award-winning illustrator and SJSU professor Alice (Bunny) Carter and Sunset magazine illustrator Lucy Cain Sargeant (later instructor at SJSU). These women were all business. Carter wrote about the client/illustrator process in designing a Star Wars game cover; she would become a legend in building the sought-after Animation/Illustration department at SJSU. Sargeant guided multiple Euphrat publications. There were people who "got it," and could speak up. For our exhibition FACES, 1984, we connected with vocal LaDoris Cordell, Superior Court Judge, Santa Clara County, 1982-2001, at the forefront of social justice; she understood the connection with art. Mary Andrade created a vehicle for art in 1978 as co-founder, co-publisher of the bilingual La Oferta, the oldest continuous Latino publication in San José. Andrade, an artist/activist and expert on Day of the Dead altar traditions, and I would discuss the importance of art in building community. I was overjoyed to exhibit her tender 1985 photograph, Juana Chavez, of Cesar Chavez's mother crocheting. Andrade's early photography and interviews of local elders inspired Ethnic Community Builders, 2007, by Francisco Jiménez, Alma M. García, and Richard A. García, about the struggle for citizenship rights in San José. 33

For decades, much of the art world was still distancing itself from communication and content. To quote art historian Moira Roth: "…the Aesthetic of Indifference was a more potent and dangerous model for the 1960s. It advocated neutrality of feeling and commitment in a period that otherwise might have produced an art of passion and commitment." We cited Roth's 1977 "Aesthetics of Indifference" essay in our publication CONTENT: Contemporary Issues, 1985. 34

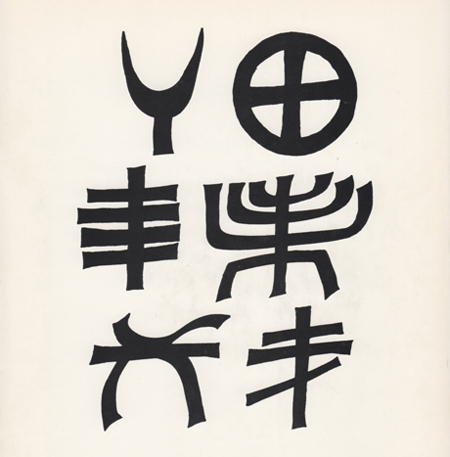

For the book cover Peretz Wolf-Prusan, printmaker and calligrapher, created Ancient Religious Symbols—crescent, earth mother, pilgrimage of the soul, menorah, Vesta, and Russian-style cross.  Wolf-Prusan's chapter treated the revival of the Ketubah, or Jewish marriage contract, an art form with calligraphy. Calligraphy of various spiritual traditions was also passed over by modern art institutions. (Fortunately Steve Jobs happened upon a Zen calligraphy class and developed a new way of seeing.) We all lost when the art world distanced itself from spiritual or philosophical issues, from exploring a range of shared core values and the accompanying questions and dialogue. How did we lose these essential connections? Investigations of fundamental human concerns occur, say, in a good literature class. The arts should play an equally important role in these universal inquiries. 35

The '80s were full of building up one's own organization and connecting with other organizations for support, at a time when government arts structures were still being built.

For example, the Arts Council of Santa Clara County started in 1982, but their focus in the '80s was on funding the "big five" arts organizations in San José. From around 1985–1988, smaller groups met monthly, often at the Euphrat, for the Arts Alliance, an Arts Council advisory group. Even when I was appointed to the Arts Council in 1988, it took a while to get smaller organizations on their radar. I met with Peter Hero, head of the Community Foundation, who understood the concerns, but said small organizations needed to "wait their turn." Meanwhile we, along with other small organizations, worked with Business Volunteers for the Arts, a new Arts Council program (1985–1986).

Also, just to get attention for the arts, people needed to start city arts commissions. With some Euphrat board members, we initiated the establishment of the Cupertino Art Commission in 1986-87. Cupertino City Council didn't approve it the first time, so we made our case again. We also worked with the City of Sunnyvale on decade-long exhibition programming at the Sunnyvale Community Center. We struggled to work with our three very different Silicon Valley cities, Cupertino, Sunnyvale, and Los Altos, each with their councils, commissions, and staff. 36

Nothing was easy. To build Euphrat art education partners and just nominal low-income program funding required long city council meetings and working with skeptical city staff. To reach families and communities, we developed ongoing programs with school districts, again with nominal funding. During the '80s we worked with faculty, staff, and school district trustees of the Fremont Union High School District and Cupertino Union School District. Among other things, we started FUHSD student shows to bolster the case of the beleaguered high school arts programs. We formed a Euphrat Board Art Education Committee, and later partnered with the SJSU art education department so we could train new graduates in community work. In the early years, partnerships were a hard sell, yet all came to enjoy the new programs and accolades that followed. With their experience, consultants Ruth Tunstall Grant and Maribel Alvarez brought a wealth of ideas to our education program and vision of a diverse arts community, including understanding of the needs of underserved populations and at-risk youth. We saw progress with the idea that responsive regional governments, schools districts, and others could partner with the arts to benefit their constituencies; that everyone, all ages, had a stake in the arts; and that there were special arts needs in some sectors, e.g., low-income. A breakthrough came in 1989, when the Euphrat was the site for a press conference sponsored by the Community Foundation, Santa Clara County Arts Council and National Endowment for the Arts to announce the creation of a major new endowed fund for small to mid-size arts organizations in Santa Clara County. While these grants were small, as were state grants from the California Arts Council, they made a difference. Recognition from a good peer review process was a prized accomplishment and critically important for small organizations pursuing diversified funding with corporate and individual support. 37

Apple supported and participated in many early Euphrat Museum exhibitions, and the Euphrat created art exhibitions in numerous Apple buildings: An extension of 1984's FACES with Luz Bueno, using Via Video System One; Lili Butler's dramatic larger-than-life sculptures, The White One and The Black One, in Apple's main lobby in 1985, the year of the Steve Jobs/Apple board clash; and 36 artists from our 1988 Art of the Computer exhibition, with works from a broad spectrum of research, artistic and commercial computer graphics. Euphrat placed exhibitions at Hewlett Packard and Tandem Computers, also. We organized an event with sculptor Bruce Beasley at the home of Hewlett Packard VP Joel Birnbaum. VPs from Hewlett Packard, Apple, and Tandem served on our Euphrat board. Steve Jobs saw the art in all he built, so I add a few thoughts about art, design, and money. Regis McKenna, whose advertising firm marketed Apple computers, chose designer Rob Janoff to create the iconic Apple logo, originally drawn by Carlos Pérez, in1977. McKenna credits artist Tom Kamifuji, Palo Alto, with inspiring the rainbow look.  Kamifuji's bright-colored, bold kabuki silkscreen posters were hot items, and we included him in our 1981 Commercial Illustrators Show. Three decades later, in 2007, we enjoyed working with McKenna when Steve Yamaguma Associates designed our lively new Euphrat logo and we prepared for our impressive new building facing Stevens Creek Blvd. In 2011, Steve Jobs presented Cupertino City Council with designs for Apple's new circular headquarters farther down on Stevens Creek. I was at city hall that night because of annual city budget deliberations. We spoke briefly, and I wish it had been about art; we had recently completed our Learn to Play exhibition about games. But Jobs was on his last legs with terminal cancer. "Everyone needs money," he said. 38

José Antonio Burciaga (1940–1996), artist, poet, and writer, and Cecilia Burciaga (1945-2013) were Euphrat Museum board members in the early 1990s. Our intense discussions about art, education, and exhibitions took place around their Casa Zapata dinner table. Together they guided and mentored hundreds. Chon Noriega describes the strategic and the magical. Regarding the particular courage of Cecilia Burciaga, professor emerita Amalia Mesa-Bains, former head of visual and public arts at Cal State Monterey, said in a Monterey Herald obituary: "If things were unjust, unfair, not right, Cecilia would take up the cause and she wouldn't back down until the problem was fixed. I would consider her one of the people who most embodied the movement toward justice."

39

Regarding traditional arts with a dispersed population, in our early efforts to connect and learn, we featured Pomo basketry and Mabel McKay in 1982, included Central Coast baskets from the collection of local historian Austen Warburton in our CROSSOVER technology exhibition in 1982, and presented Art of the Bear Dance, A traditional Spring ceremony of the Maidu Indians in 1984. In 1986 the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe constructed a tule house for the de Saisset Museum, and subsequently contributed to public art projects, such as the Ohlone/Muwekma Tribute along the Park Avenue Bridge in Guadalupe River Park & Gardens. More recently at the de Saisset Museum, Director Rebecca Schapp has overseen renovation of their California History exhibition and a new iBook, which focuses on the history of Santa Clara from pre-European contact. 40

Underwood is attuned as Latina, Chicana, and Native American. Many of her weavings honor the indigenous Yaqui, whose homelands were cut open by the U.S-Mexico border. She was one of our "tell-it-like-it-is" board members.

41

Published by Cultural Initiatives Silicon Valley, the book was the result of a second study commissioned by John Kreidler. As Executive Director of Cultural Initiatives Silicon Valley from 2000-2006, Kreidler worked to implement a 10-year cultural plan for Silicon Valley. In 2004, CISV commissioned cultural anthropologist Dr. Pia Moriarty to examine informal performing arts groups in local immigrant communities (Immigrant Participatory Arts: An Insight into Community-building in Silicon Valley). CISV's final project, Medici's Lever, 2009, was an online suite of two games and one simulation laboratory probing regional cultural policy. One of the games is entitled SJ Renaissance. For more information see interview or go directly to Medici's Lever. 42

For a larger context, artist/faculty member Carlos Villa was the organizer and producer of "Sources of a Distinct Majority," a series of four heated symposia at San Francisco Art Institute, 1989–1991, that upped the pace of moving past stale structures. The publication Worlds In Collision, drawn from the symposia series, includes "diverse concerns of artists, activists, academics and street scholars from both ethnically marginalized and mainstream communities throughout the country. These four symposia, organized around issues of multiculturalism, education, identity politics and the role of the arts in contemporary culture, became venues for intense dialogues with broad implications for rethinking the relationships around cultural theory and activist agendas. The nearly 90 participants collectively and collaboratively explore strategies for a progressive art agenda that reflect a more accurate American Art History." I participated. It was invigorating to explore new strategies collectively. The concurrent Global Cultures, the 1990 Congress of the Arts, Los Angeles, described California: "Its successes and failures at managing the issues posed by ethnic diversity and interdependency with the global economy are a proving ground for the rest of the world." While I didn't attend, the event, sponsored by California Confederation of the Arts, helps understanding of context. Subtitled "A Challenge for the 1990s," this pragmatic gathering centered on government, business, foundations, and the arts, and included a mini-conference on "Art and Disabilities." 43

To give an idea of demographic changes, in 2000 the ethnic makeup of the county was roughly 54% white, 2.7% black, .7% Native American, 28% Asian or Pacific Islander, 24% Latino. In 2010 the three largest population groupings changed to 35% white, 32% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 27% Latino.

44

Also in October 1995, a public meeting on multicultural exhibition collaborations was held in San José. As Joe Rodriguez (then of the San José Office of Cultural Affairs) put it, the purpose was "to identify issues relevant to collaborations between San José-based multicultural arts groups which lack exhibition spaces, and visual arts organizations with space to house exhibitions."

45

With a welcome by County Supervisor Dianne McKenna, the two panels included Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Tito Gonzales, East Palo Alto City Councilwoman Myrtle Walker, and artist/educator Ruth Tunstall Grant. Arts Council director Davis worked with an arts/activist staff that understood grassroots: Diem Jones, Lissa Jones, and Audrey Wong. 46

Consuelo Santos Killins spoke up in multiple ways. She promoted Northern California on the CAC, which has been dominated by Southern California. At a CAC meeting in 1989, Killins wanted to serve "all the people of California," and stated, "This is the last time I'm going to vote to fund applications for large-budget organizations unless board of directors' makeup starts to change radically." Advocacy normally isn't "speaking to the choir;" there is an element of activism, standing up to power on behalf of individuals. One of our Euphrat board members, Judy Goddess, used to work on "Individual Advocacy" for parents and kids having problems with public schools. She relates the joy of "bringing a system around to give a service a kid deserves." Where would we be without such advocates for the arts, education, for the marginalized, for those in need? This advocacy can also arise with active participation in a commission, nonprofit, or startup group. 47

Countywide, Adobe supported graphics grants. Applied Materials supported "Excellence in the Arts." Under director Bruce Davis (1994-2011), Arts Council Silicon Valley made great strides in helping fund diversity, increasing seed funding to small and mid-sized organizations. 48

MACLA and ZERO1 with its biennial festival have hit the big leagues. Cultural Initiatives Silicon Valley (1996-2006) inspired by Mayor Susan Hammer, a leader in regional cultural planning, brought movement on cultural policy and art education. Then 1stACT Silicon Valley, 2007, a high-end, five-year hybrid, leveraged a "network of networks" for leadership, participation, and investment in art, creativity, and technology. Silicon Valley Creates, 2013, is a merger of the Arts Council with 1stACT, with multiple programs. Enlightened government is a boon to cultural life, when it's lucky to have someone like Barbara Goldstein, San José Public Art Director, 2004-2013. I worked in recent years with Goldstein on the City Hall Exhibitions Committee, with Ruth Tunstall Grant from the Arts Commission serving as chair. One of our first exhibitions in City Hall connected art, history, and research, with a spotlight on artist Mary Parks Washington and ties to the local African American community going back to the 1800s. 49